What Do You Do with Beauty?

06.06.2013 Features

Wendy Richmond

In this article originally published in Communication Arts May/June 2013 Issue, Wendy Richmond wonders if our need to own and share beauty deepens our connection with it, or takes away from it?

There is a mile-long stretch of the Maine coastline that I have come to love; I especially look forward to seeing its splendor change with every season. Last summer, on an early morning walk, a white rainbow appeared, and it literally took my breath away. I witnessed this exquisite phenomenon with dueling feelings of awe and agitation. Yes, I wanted to simply look at the rainbow, but its beauty also made me want to do something with it. As humans, we have the good fortune to know and appreciate beauty. And alongside that appreciation comes other human traits, such as the need to own, share, protect and/or create with it. Does that need (and its subsequent action) deepen our connection with beauty, or take away from it? The more I ponder this conflict, the more curious I am about its complexity.

Capturing beauty

When I saw the white rainbow, my instinct was to pull out my cell phone and take a picture. At first I felt annoyed at my phone for inserting itself between me and nature. But then I realized that the impulse came from a desire to hold onto and expand my connection, and in this regard, the cell phone was both a culprit and an ally. In 1998, I wrote a column titled “Visual Episodes,” and referred to Susan Sontag’s classic book On Photography. Sontag described photographing as a means of attaining ownership: “To collect photographs is to collect the world.” She wrote, “Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood.” Around the time I wrote my column, I was traveling in Italy, using a point-and-shoot camera to “collect” abstract forms that I found to be uniquely stunning. Not only did I want to have, and keep, those beautiful forms, I also felt that by making them mine, I developed a heightened awareness of my aesthetic vision. But now, many years later, I wonder: Are my photographs just souvenirs that I acquired during my journey, not unlike the leather gloves and silk scarf I bought while I was there? Did I miss out on truly absorbing beauty because I was determined to take it with me, as opposed to concentrating on the real-time experience? Ownership (which can be broadly defined) is one way of connecting with beauty. Whether it adds to or subtracts from one’s bond

Sharing beauty

In her popular book Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, Sherry Turkle wrote, “Technology makes it easy to express emotions while they are being formed. It supports an emotional style in which feelings are not fully experienced until they are communicated.” On one hand, I see how technology lessens our connection with beauty. Turkle suggests that we need to communicate in order to know what we feel. And so, before we even give ourselves a chance to hold and comprehend beauty, we send it away: we export and expunge it, via text, post or Instagram. On the other hand, the act of simultaneously seeing and sharing can enrich our appreciation of beauty. When I looked at the rainbow, I knew what I felt: joy! And I wanted to express that to people I care for. I wanted them to have some part of it, and why not right away? So, again, an external tool was poised to be both my aid and my distraction.

Collaborating with beauty

Some of our most profound interactions with natural beauty are experienced through works of art. One of my favorite places to see collaborations between artists and the landscape is Storm King Art Center in New Windsor, New York. Sculptures there have employed natural materials, like Maya Lin’s Storm King Wavefield and Andy Goldsworthy’s Wall That Went for a Walk, as well as contrasting materials, like the steel plates of Richard Serra’s Schunnemunk Fork. We understand beauty through their efforts to understand it. As Goldsworthy says, “I’m trying to get beneath the surface appearance of things. Working the surface of a stone is an attempt to understand the internal energy of the stone.” For those of us with art-making in our DNA, this collaboration includes the compulsion to make our mark, convey a stance, or perhaps encourage an audience to see something more. However— and here I am speaking for myself—this urge is also presumptuous, an act of hubris. What mark could I make that would not detract from what is perfect, let alone add to it? In this conflict, I always hope that the urgency to connect with beauty is stronger than the fear of thwarting it. ca

© 2013 W. Richmond

Reprinted with permission by Wendy Richmond, All rights reserved.

This article first appeared the May/June 2013 issue of Communication Arts

Communication Arts.

About the author

Wendy Richmond is a visual artist, writer and educator whose work explores public privacy, personal technology and creativity. She began mixing traditional and new media at MIT, and co-founded the Design Lab at WGBH. Her teaching includes Harvard University, International Center of Photography and Rhode Island School of Design. Richmond’s installations have been shown internationally, and she is the recipient of a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, a Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center residency, a National Endowment for the Arts grant, and the Hatch Award for Creative Excellence. Her newest book is Art without Compromise*. Her CA column began in 1984Wendy Richmond.com

relatedarticles

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

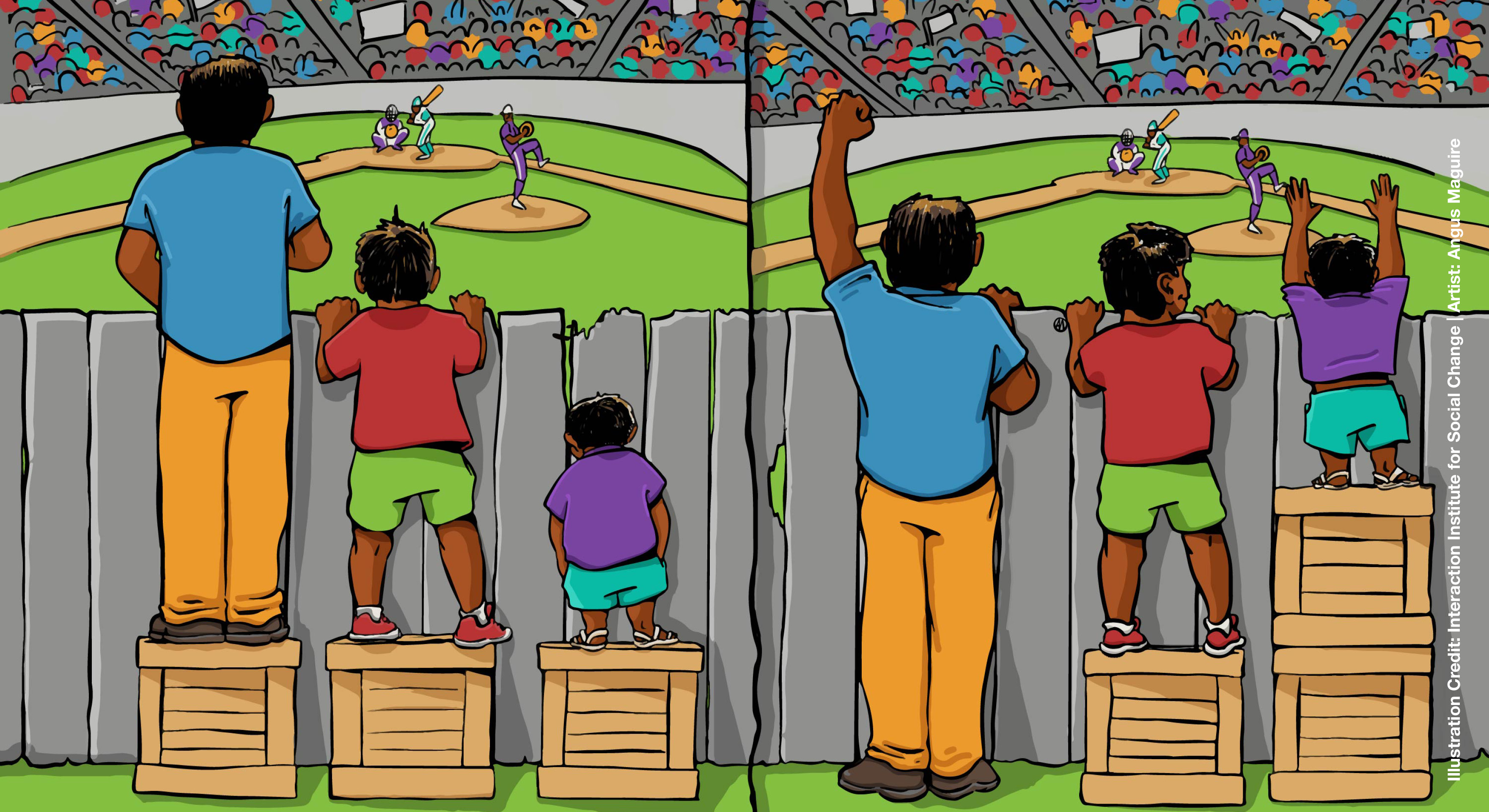

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)