Kindling

13.10.2011 Features

By Victor Margolin

Communication design starts historically from book design. Today editorial design (books, magazines, e-publications, online journals, etc.) is still core to the profession of communication design. This editorial by Victor Margolin regards the evolution of the Editorial industry and commerce, knowledge transfer culture, intellectual property, publication design and many other issues that influence our profession intimately.

We live in the age of information but there is a paradox. Just as we appear to be confronting information overload, information is also disappearing, at least in its hard copy form. Advertisements for the Kindle and its copycat versions tell us how efficient they are. In one ad, we see a young man and young woman talking about a new book that interests them both. The woman says that she is on her way to a bookstore to see if the book is available, while the young man, with a click of an icon on his e-reader summons the electronic version to his screen immediately. The young woman is impressed. We, of course, are supposed to applaud the efficiency of the e-reader and appreciate the reduced price the young man has paid for the e-version of his book.

What we are not told in the ad, however, is that the young man does not actually have full ownership of his e-book. He has the right to read it on his device but in most cases he cannot pass it on to a friend, sell it to a second-hand e-book store, donate it to charity or do any of the things with it that the owner of an actual book can do. Besides, Amazon, or whoever sold him the e-book has a record of his purchase and can make that information available to others as it sees fit.

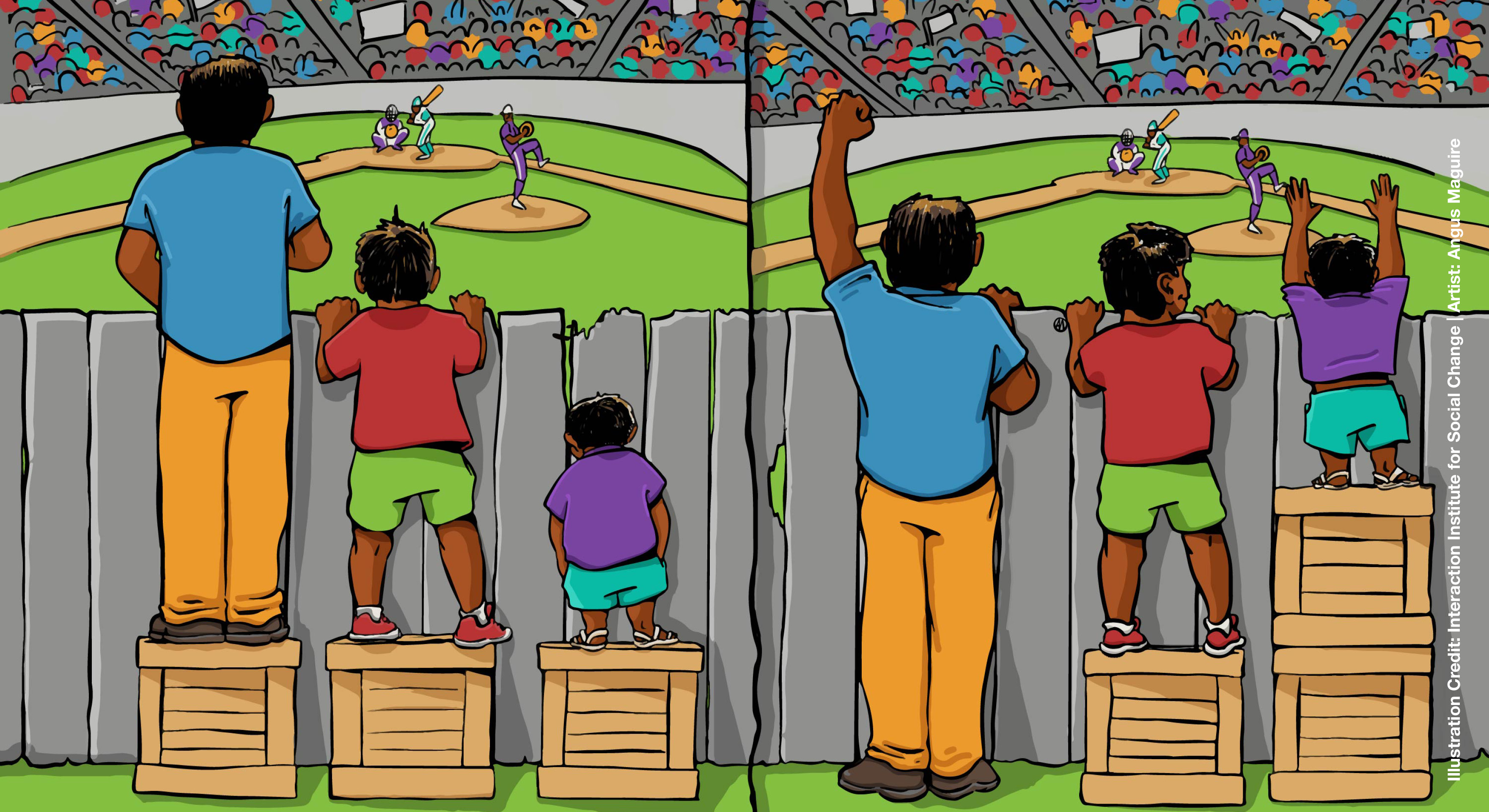

The main point I want to make here, however, is that e-books eliminate access for all of us who do not possess e-readers and choose for our own reasons not to have them or to pay for e-book downloads on our computers. By reducing the number of actual books that are sold, e-books cut into the circulation system that makes real books available in a variety of settings after they have been read once by the initial purchaser. In fairness, I do want to note that more and more libraries are making e-books available to patrons who have their own e-readers. The downloads are programmed to last for several weeks and then expire. At present, however, most of these download programs are compatible with Sony readers only and not with the Kindle. Whether Amazon will agree to allow free access to e-books from public libraries remains to be seen.

Purchasing books at a used bookstore makes them available at reduced prices. Their presence in such stores also means that a book might be discovered serendipitously by a browser who otherwise would not know of it. Many people donate used books to schools, hospitals, and other institutions where folks cannot afford books and finally all of us like to loan books that we enjoy to friends. By competing with hard copy versions whose fates are in full control of their owners, the e-book culture reduces access to books for many people.

We have already witnessed the loss of music stores such as Tower Records and the Virgin Music Stores, due to the mass attraction to downloading MP3 versions of songs and albums, and should note that this is happening as well to bookstores. Borders, a national American bookstore chain, recently declared bankruptcy and closed several hundred stores. Barnes & Noble, the other large American chain, is barely hanging on, partly because it has its own e-reader and on-line e-book store but you can be sure that when e-book sales reach a tipping point, Barnes & Noble will also fold.

As if the loss of books is not enough, we might also worry about what is happening to academic journals. In the sciences as many have pointed out, publishers are charging exorbitant prices for access to articles but in the humanities and social sciences, the situation is somewhat better, although not without problems. Of course, some journals are published electronically and are available free but others are not. Many journals are archived in databases like Project Muse and J-Stor. They are free if you have a password but you can only get a password if you belong to an institution such as a university that has purchased access rights to that particular database. If the university also buys the journal, well, that's not a problem. You can go to the university library and read it there but if it is not available in the library and you are not part of an institution that subscribes to the database, then you cannot access the journal. This means that independent scholars and others who cannot afford to pay exorbitant amounts of money to purchase copies of single articles will not have access valuable research material.

The digitisation of cultural artefacts, whether books, journals, CDs, or movies has embedded our experience of them in systems of control that have, in fact, significantly reduced our right to use these artefacts as we wish. I recall an incident several years ago when a friend was helping me make a short QuickTime film for which I wanted to use a jazz tune, "Wagon Wheels," by the saxophonist Sonny Rollins. I purchased the Rollins album Way Out West in an MP3 version only to find that I was unable to fade the song I wanted in and out. I owned the digital album but had no control over how I could use it. I therefore had to go to a music store and purchase the original CD in order to use the music as I wished.

How to remedy the situation? First of all, we should not be so quick to jettison hard copies of books and journals or for that matter CDs. There are important ways that hard copies of any cultural artefacts circulate that will be eliminated if we embrace their e-versions to heartily. Second, we need more open source access to academic journals. After two years, why not simply make them available free on line and forget about the additional income that has as a consequence keeping them out of broad circulation?

The main point of this digital revolution, however, is that it is radically changing the way we share culture. Instead of ensuring at least some free access to everything that is produced, we tolerate the production of artefacts in digital forms that limit what we can do with them. A supplier can even yank an e-book off our reader if it claims just cause. This occurred not long ago when everyone who bought a particular e-version of George Orwell's novel 1984 from Amazon discovered that it had disappeared from their Kindles because Amazon had a copyright problem with that particular edition of the book. In that case truth was not stranger than fiction but was no less strange.

About Victor Margolin

Victor Margolin is Professor Emeritus of Design History at the University of Illinois, Chicago. He is currently working on a World History of Design.

tigger.uic.edu/~victor

relatedarticles

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)