Where our wild things are, Part 2

02.06.2010 Features

Ethics in an age of exacerbation

DK HollandThis second part of a two-part series written by DK Holland for Communication Arts magazine discusses the varying approaches and opinions surrounding design ethics, from work for hire to unsustainable design. .

About 20 years ago, a 30-something graphic designer, a leader in the profession no less, scoffed at me, "Why do we need to talk about ethics? You either have them or you don't." But ethics is neither black nor white. The whole point is, there is no easy, good choice. Did this designer speak for the profession? Perhaps. Fast-forward twenty years. At no time has a working understanding of ethics been more essential because it is so lacking.

Law and order

Since professional ethics is about fair and balanced decision-making, ideally that means good ethical thinking promotes the overall health of the community (e.g., practitioners, clients and the public). Therefore you may do something that is totally legal and yet quite unethical if it is unfair to part of the community.For instance, if all graphic designers, illustrators, photographers were to understand that what they sell are rights, then the standard practice of selling rights would be preserved - and with it, some ethical standards. But if too many practitioners give their rights away for cheap or don't pay attention to what they're selling, then the whole profession gets sloppy: The community is tarnished, out of whack, hence demoralised. That's what has happened. The public is clearly not enriched by inferior design; most clients don't necessarily count design as a valued asset; and designers cannot subsist on what they are making. The profession's essential support - the associated institutions and companies who rely on designers and design to thrive - is also threatened.

It's complicated

Agility of the logical/emotional mind is key to making confident decisions. It's the role of the logical brain to rein in emotions. Recognise reality. The emotional (subconscious) brain, while creative, does not make ethical choices and doesn't understand intentions.The client is the 900-pound gorilla in the room: He smells both fear and confidence. Designer Stefan Sagmeister balances the needs of the client with his own when he decides which rights he will sell or retain. He says, "We are working in all models: For the music industry, all the rights are transferred to the client (I remember a Warner Brothers contract that included the phrase '...throughout the universe including media yet to be discovered'), all the way to corporate models where we discuss the scope of media and timing when estimating and then charge extra when the scope is widened later on. On self-initiated projects, like the Things I have learned in my life series, we retain all rights." Understanding the long-range impact of any agreement from the gorilla's point-of-view as well as yours requires a mature, informed point of view.

Dance Fever

The Joffrey Ballet hoped for something truly innovative when they recently posted a project on CrowdSpring.com, offering $700 to the winning designer for its new gala invitation. CrowdSpring is an online brokerage that claims to have 50 000 designers eager to design your logo, brochure, whatever, all on speculation. Some perspective: 50 000 is 2.5 times the number of members in the AIGA and 50 times the number of members in the Graphic Artists Guild, two of the organisations that protect the health and well-being of graphic design. Posting the project on CrowdSpring seemed logical to the Joffrey, a well thought of cultural institution in Chicago. After all, they find their dancers by audition.While a huge number of designers are unemployed, and design firms are universally hungry for work, CrowdSpring claims it provides a service to the community, which, it says would otherwise not have access to "quality design and designers." [1] Designer Lance Rutter of Legendre+Rutter, a past president of AIGA Chicago and just one of the many who expressed indignation, says, "I've had designers unabashedly say to me, 'I do it - so what? I do it quick and cheap by using stock photos. They've even admitted to 'ripping off' another designer's style or idea." An average of 77 solutions are submitted to CrowdSpring for a project, from which the client chooses one. Rutter says, "That means there is a 1.3 percent chance that your solution will be selected; a 98.7 percent chance it won't. How thoughtful or relevant can your work be?" Where is the quality? Did the 77 designers who submitted have rights to the images they used in their comprehensives?

CrowdSpring covers itself. Any liability falls to the winning designer, who must sign a Works Made for Hire (WMFH) agreement, which means CrowdSpring and its client are free to go on to exploit the work without any additional benefit to the designer who created it.

Rutter observes, "Now there is a middleman who sees design as a profit center. They see they can take advantage of designers, who love what they do. This facilitates bad ethics."

The 900-pound gorilla has an armload of law books. And so an understanding of the law, in particular, the Copyright Law, often called the Creator's Law, is obviously important to the success of the designer as well. The bugaboo of that law is the highly questionable WMFH loophole (which is unique to U.S. Copyright Law). When asked if he has ever signed WMFH, Sagmeister says simply, "Yes, I have." Sometimes it's not a bad move. But usually it is.

Works made for hire

An independent creator, except when working in certain narrow categories [2], is not legitimately working for hire. But, to totally protect their own interests, lawyers tell their clients to get WMFH agreements signed, regardless.In order to be considered legal, WMFH must be agreed to in writing by both parties before the work starts. But if you are going to sign away all your rights and your sketches and the right to alter your work, and the right to get credit for doing the work and any other creator's sketches, rights, credit used in the creation of the work, perhaps, just perhaps, you (and any other creators involved) deserve additional compensation. And what about sales tax? So if you look at the community - the public, client, shareholders, the creator(s) - are any well served by a blanket use of WMFH? [3]

On the other hand, any employee who is provided benefits and salary works for hire. In exchange, you put all your best efforts into the work of your employer, whatever the project. In the bargain, your employer becomes the creator. It's understandable. The employer is protecting the company's interests (and your job). But you, the employee may, in a way, become invisible as a result.

Brad Weed, designer and employee of Microsoft, sees it differently. He explains, "The work of the collective is much more exciting than working on your own. You don't care if it's your idea or your co-worker's. The end goal is the consumer's enrichment. That's what I love about working at Microsoft." Microsoft also understands its employees' need for personal achievement and so encourages them to apply for patents in their own names. Any relationship has to be reciprocal to be truly successful. Balance and fairness.

Ironically, among those who do not get this is our U.S. government. The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) recently held a design contest. Pretty much anyone could submit designs. The award was reasonable - up to USD $25 000 for a new logo. It would call for the winner to sign a WMFH agreement (an all rights and title transfer - a 'buyout' would have accomplished the same thing and not been offensive). But the real ethical issue was the disrespect the NEA showed for the work of the design field by asking just about anyone, pitting rank amateurs against pros to participate. A cattle herder could rustle up a logo. A pastry chef could bake you a mark. Why not?

The response from designers was uniform disgust. At a time when the business of graphic design was unstable, the NEA was pulling the rug out from under it. The final insult was a requirement that the new NEA logo show that "Art Works" is a reminder that "arts workers are real workers who are part of this country's real economy. They earn salaries, support families, pay taxes." Not if they must work for free, NEA. [4] Like the Joffrey, the needs of the entire community were not considered.

Rutter, who uses a contract with any significant client, says lopsidedness can go further. "There are clients who won't let you work for any of their competitors, nor show the work you've done for them. I agreed to work this way with one large client. The tradeoff, the huge amount of work they promised, never materialised. I asked to be taken off their list. You learn from your mistakes."

Stock logos

Another hot button is the plethora of Web sites that sell logos for cheap, sometimes almost for free. Why would anyone want to work this way? You get what you pay for. Designer and Pratt professor Tom Dolle (and owner of Tom Dolle Design) says, "We've found that when we assign projects to students they are far more complex these days. There is no stock answer." Recently How and Print magazines sent a promotional e-mail out from one of its clients which promoted stock logos. This resulted in, as publisher Gary Lynch says, "A firestorm of anger and disappointment over how two well-respected brands could endorse something that violates and threatens the basic principles of graphic design. Our editorial teams, who were unaware of the promotional message were equally outraged, as it reflected poorly on their brands. And all of the outrage is justified." Lynch apologised saying, "I can state unequivocally that [this] e-mail [did] not reflect How and Print's sensibilities in regards to the integrity and importance of graphic design." So the "designers" creating cheap logos, and those signed up on Crowdspring - What do they read? Where did they learn design? Why don't they get the problem here?Lynch's swift response to this unfortunate oversight was commendable and raises a point. Besides the organisations (which have legal limits), can the respected brands of design - the publications, schools, publishing imprints - help provide leadership and turn the profession around? Or is the cockpit empty? Aren't we headed for a crash if no one takes control of the plane? Designers cannot make a living (nor can they pay for subscriptions, dues, buy books, pay tuition) by selling stock logos at $5 a pop.

Since graphic design has become commodified, many graphic designers have reconsidered their monikers, calling themselves information architects, creative directors or communication designers. Designer Michael Cronan, who has evolved to become a brand strategist, says, "Shallow thinking does not make the world better. It's a waste of everyone's time. Your logo is your hardest working employee. It makes no sense to undervalue your identity by trivialising the process." He adds, channeling Alan Watts, [5] "Unless there is a value exchange, nothing happened."

Cronyism

In the 1960s and 1970s, a few iconic New York men largely defined a new field called graphic design (nee commercial art, The Journal of Commercial Art was also the original name of this magazine founded in 1959) in the United States: Milton Glaser, Ivan Chermayeff, Massimo Vignelli, Seymour Chwast, Robert Brownjohn were among the pioneers. Some are, fortunately, still with us, still designing. Back in the day, there was a publication called U&lc, designed by another man, legendary type designer Herb Lubalin. It was all about the men. More men emerged. In the San Francisco of the 1970s and 1980s all eyes were on the five Michaels (Vanderbyl, Mabry, Cronan, Schwab and Manwaring). All of these men were successful, white, middle class designers and illustrators. Often their best-known work took the form of posters, logos, very powerful, beautiful, single images. Few people outside of the design world, however, knew more than one of these men. This may have partly been the result of insularity, a kind of cronyism.Many of the men became leaders, teachers and/or board members in the design organisations, in particular, AIGA, devoting their time to steering the profession. Fast forward to 2000, 2010, the era of USA Today, YouTube, and although many people now have a vague idea what a graphic designer does, few can name a graphic designer of note. Ric Grefé, executive director of AIGA, points out that graphic designers do not play a role in public life. He says, "Graphic design is so valuable to society and business. To be able to contribute, however, designers should be recognised as peers not specialists within their communities. Yet designers do not pursue either visible or leadership roles in their communities. For instance, there is not a single graphic designer elected to any public office that I know of. And still designers expect the public to appreciate what it is they do."

While there are now an estimated 300 000 graphic designers in America and over 50 percent are women, the racial representation is still skewed heavily to Caucasian. Grefé looks at the homogeneous make-up of the design profession and says, "The twentieth century economy and brands were so strong that good design could succeed in the global commerce driven by the U.S. regardless of the cultural make-up of the consumer. Now we are facing a new global economic paradigm, without the U.S. as its sole pillar, and there is cultural pushback. Designers have to experience people different from themselves in order to design for a diverse audience. When the design profession looks like the population as a whole, then we will be successful. The genie is out of the bottle; the new normal is not the old normal."

A subscriber to the new normal, designer Armin Vit, UnderConsideration, says, "Designers have become independent because of the Internet. You don't need to belong to an organisation anymore. The little brochure that used to come in the mail from the organisation that told you how you are supposed to work is antiquated. People are seeing what others are doing, making their own rules. There is greater transparency." He adds, "People read blogs a lot more than magazines. That's where they get their information, figure things out." Maybe the CrowdSpring "designers"? The stock logo designers? While design juries historically elevated an individual designer within the profession, now anyone can see the work of any designer since it's all online. It's easy to make snap judgments.

In the past, a community of designers clustered together which led to elitism, exclusivity. Now there is a vast sea of people calling themselves designers, no names, not connected through any organisation. Cheryl Heller of Heller Communication Design who resists calling herself a designer, says, "Graphic design as we know it does not have a robust future. It had become so insular that we'd convinced ourselves the rest of the world appreciated it in the same way, that talent was the distinguishing factor. Inevitably talent became easy to find. It's like designers said, 'We're too special to have this happen.' Yet it did. We need to figure out the next frontier." Heller adds, "Systems thinking, strategy, is where that value is. Those are skills that will not be outsourced or crowd sourced."

With all of its mundane ubiquity, is cronyism still an issue in graphic design? Absolutely. There are still some high-profile designers referring other name designers for awards, positions of stature. Since highly visible, sexy design projects are even rarer than before, some high-profile designers use their clout and glamor to undercut other designers. They have no interest in seeing the movie they have starred in come to an end. But it is. Heller, 2009 chair of the AIGA Gold Medal says, "Wouldn't it be better if we established real metrics for winning a medal? The larger and more diverse a community, the greater weight the award would have."

California State University Chico professor Barbara Sudick says, "Cronyism also exists in the form of influence peddling and the currying of favors. A designer gives a printing company a certain amount of work, not even the printer best suited for the job, then the designer goes back and asks for a give-back-free self-promotion, business or holiday cards or a job printed for free for a friend."

Could graphic design, which started as a trade, have been elevated to a profession if it had not dismissed licensing as a way of legitimising the field? Is the horse out of the barn? Firms that are thriving do not consider their work to be pure graphic design anymore. They realise their value is in big picture thinking: taking in the considerations of the whole community.

Unsustainable design

In the early to mid-20th century, planned obsolescence (i.e., stimulating wasteful demand) emerged to help save the U.S. economy from a lingering depression. Graphic design became a partner in crime in what designer Tibor Kalman called the "churn," by seductively restyling and over-designing packaging and promotion simply to gain the consumer's attention to buy, buy, buy. Designers became producers of eye candy.But many designers see things differently today; there is a need to balance profit and sustainability, come up with solutions that don't deplete or harm the environment, but still inspire and create profit. "Designers cycle in and out of client projects pretty quickly because of the traditional design consulting model," says designer Valerie Casey, founder of Designers Accord, the goal of which is to "galvanise the creative community around social and environmental impact." [6] She adds, "Our work is often incremental, and our responsibility for outcomes limited, so we tend not to understand the full systems we are designing for. I'm not discouraged. Two-and-a-half years ago the conversation was about recycling and choice of materials. Now we're considering the consequences of our design. We're creating new collaborations, partnerships and business models. As we recreate ourselves as systems thinkers, we'll need to help our clients to work differently with us and fully understand the powerful contribution design can make." Designers Accord was given a Sappi Grant this year which posed a dilemma: Designer Scott Stowell, Open, was faced with creating the Designers Accord piece funded by a paper company. Stymied he says, "We have to have a really good reason to produce this. It can't just be print for print's sake."

Sudick says, "There's a lot of 'green washing' going on - where someone is disingenuously spinning information about products to make them look socially responsible and they aren't. Designers need to smarten up - to consider the whole supply chain, for instance, the use of child labor."

Understanding abstract concepts is relatively new to most humans, as in the last 100 years. [7] Our ability to care about the impact we might have on people we don't even know is also something new. Learning to care about a future in which we no longer exist that will help pull us forward: to not be governed entirely by the here and now. And while it may not feel it at times, the overall intelligence quotient of humans is increasing every decade. We have the ability to adapt. There is, in other words, hope for change.

An Education

We are fascinated by films, books and plays because of the ethical dilemmas that are inevitably woven through the plot and subsequent decisions that the characters are forced to make. Succeed or fail, we admire them for facing the challenge. Yet it's by repetitively examining awkward situations from many points of view that we prepare ourselves to face our own dilemmas. [8] Perhaps that's why, in our own professional lives, ethical issues get short shrift; ethical graphic design has become an oxymoron.In Where the Wild Things Are Max takes control: He faces his problems and empowers himself. And when he awakes, he gets his meal - which is "still hot." We like happy endings to our films, whether they are realistic or not. But the reality is for graphic design: It's time to face our problems. Wake up. Grow up. Hot meal or not.

Notes

- www.chicagobusiness.com/cgi-bin/mag/article.pl?articleId=32978

- A "work made for hire" is (1) a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment or (2) a work specially ordered or commissioned for use as a contribution to a collective work, as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, as a translation, as a supplementary work, as a compilation, as an instructional text, as a test, as answer material for a test, or as an atlas. (17 U.S.C. § 101)

- The state of California passed a law requiring that clients pay benefits to creators who sign WMFH contracts. Other states have not been so successful, sabotaged by more powerful publishing lobbyists.

- Graphic Artists Guild Competition guidelines are published in the Pricing and Ethical Guidelines handbook.

- Alan Watts was a new age philosopher most notably the writer of This is it.

- www.designersaccord.org

- Radiolab, Overcome by Emotion, WNYC.

- Where do you draw the line? The Ethics Game AIGA 1993 provides these exercises. It has been out of print for ten years.

Reprinted with permission by Communication Arts, ©2010 Coyne & Blanchard, Inc. All rights reserved. www.commarts.com

![DK Holland [Image: DK Holland]]() About the author

About the author

A graphic designer for many years, DK Holland is based in New York City. She was a partner in several design firms including Pushpin. Writer, editor of many books on design including Design Issues (based on her popular column of the same name in Communication Arts), DK also wrote the book, Branding for Nonprofits: Developing Identity with Integrity. She thinks about ethics a lot which she also teaches in design schools internationally. www.dkholland.com

relatedarticles

03.14.2022 Features

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

05.27.2020 Features

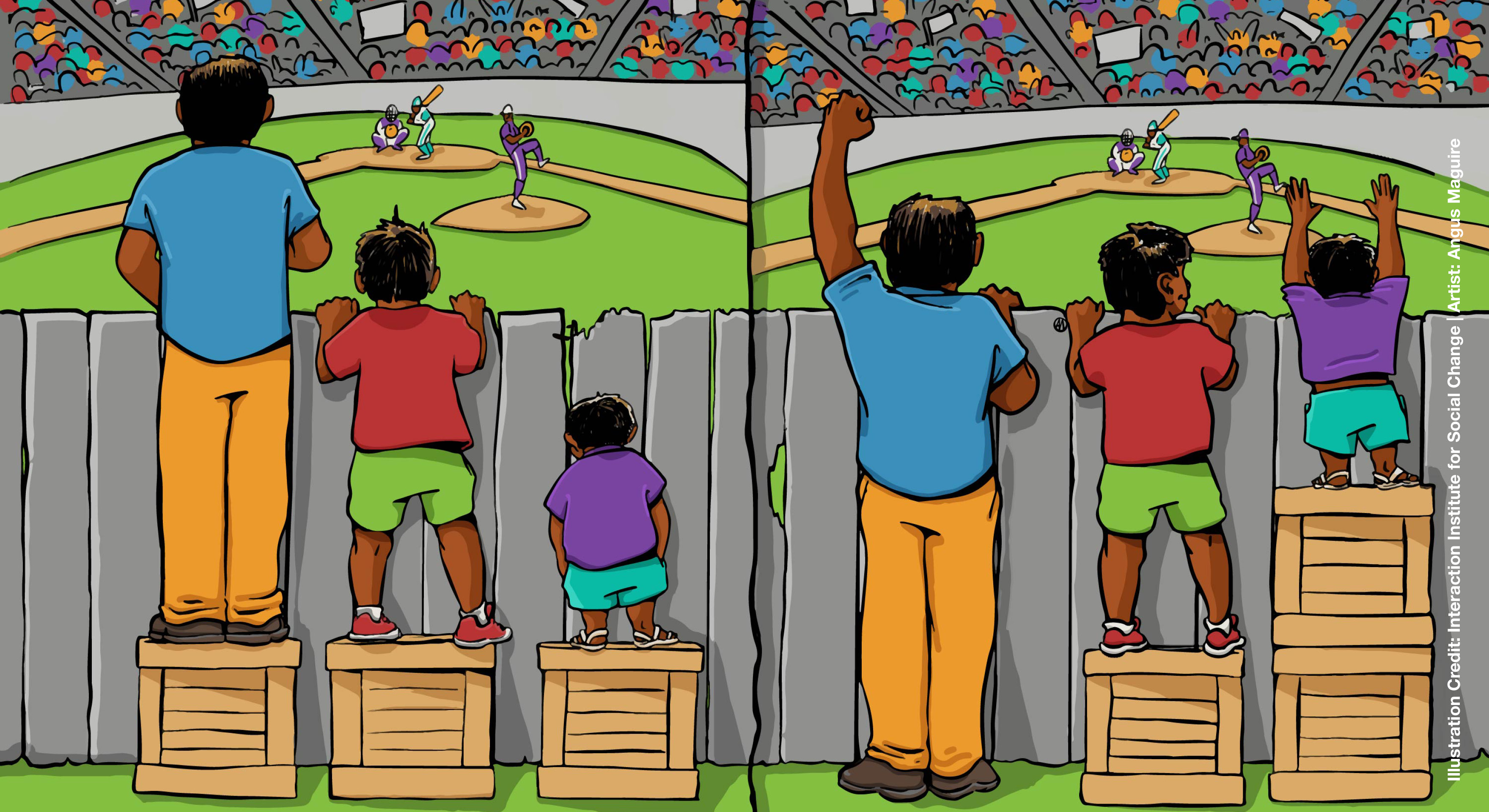

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

05.16.2017 Features

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

12.14.2016 Features

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)

05.11.2016 Features