Interview: Tim Brown of IDEO on 'Design Thinking'

05.01.2011 Features

In this interview from , Iliyas Ong looks at 'design thinking' with IDEO president, Tim Brown. Brown explains how design thinking is a way to leverage innovation and address bigger challenges and issues worldwide, a tool essential to the success and growth of any organisation.

"The problem with design," declared IDEO president Tim Brown at a lecture in Singapore recently, "is that it got small." He is speaking about 'design thinking,' a philosophy that aspires to make design 'big' again. Before his talk, Iliyas Ong sat down with Brown to find out more about his beliefs as a designer and innovator.

The Palo Alto-based IDEO is one of the largest 'design consultancies' around, with offices in Chicago, London, Shanghai and other top cities. Among its leaders include David Kelley, Stanford professor who helms the d.school, and Bill Moggridge, inventor of the world's first laptop computer. Voted by Bloomberg BusinessWeek as one of the top 25 most innovative companies in 2006, the firm, amazingly, does consulting work for the other 24.

IDEO isn't your normal design studio. There are no typography-obsessed graphic designers fretting over kerning, no web geeks arguing about Flash and HTML5. Instead, IDEO goes back to the earliest tenet of design: solving problems. It helps companies find innovative ways to develop and grow, be it by reshuffling its corporate infrastructure or oiling up service practices. And it uses 'design thinking' to do so.

![]()

"At its simplest level," Brown explains, his tone sprightly despite the jet lag from an eight-hour flight, "it's about using the processes that designers have used for many years but applying them to a broader set of challenges both in business and society."

If it sounds vague, it probably is. Brown confesses to have not "ended with any definition" to design thinking, even after publishing his acclaimed book, Change By Design, on the topic.

One thing's for sure, though: Brown knows exactly what went wrong in the design world. "Design used to be big. But then designers got preoccupied with creating small, nifty objects," he says. When Brown talks about 'big', he isn't talking about size, or scale, or depth. It's the totality of experiences that he - and 'design thinking' - refers to.

That cup you're holding, the MacBook humming on the table in front of you... these objects are works of design, but that's that. Design isn't about a fancy new computer or any 'revolutionary,' 'magical,' or 'cool' product.

Design is a "much more complex thing than any single object", Brown insists. It's about solving the problem of distributing clean water in poor countries, coming up with more efficient ways to direct human traffic in buildings, realising untapped channels of communication in trade. Design is huge.

"Designers have known this for quite a long time," Brown said. "But the business world and the world in general is just starting to understand that. Businesses especially started to realise that it wasn't good enough just to design a good product. If the service around the product was no good, or if the brand or communications were no good, you have to start thinking of them all together as an experience."

And that's where design thinking comes into play. It helps people and brands map out and focus their energies into innovation, a practice much-needed today. "As the markets opened up and technology sped up, companies get disrupted fast," Brown argues. "So whereas businesses 50 years ago could be somewhat complacent, no company could do that today."

Design thinking, then, isn't a panacea to business woes - innovation is. "It's an essential nature of all organisations if they want to be healthy and successful, that if they don't grow and change and innovate, they'll be commoditised," Brown states confidently. "There are only two potential futures for any organisation: either you innovate and grow, or you get commoditised and ultimately die."

A trip through IDEO's client list reveals a longstanding tradition of providing innovation to companies that need it most. The consultancy worked with HBO a few years ago, a time when the YouTubes and Hulus of the online world made HBO seem old and even worse, obsolete.

"HBO was very interested in looking at a design-based approach to understand how they could show up on new networks instead of being just a cable network," explains Brown on the spark HBO needed to stay on top of the media game. As a result, IDEO strategised new services and experiences the cable company could give its customers - how they could show on mobile phones and on computers, for instance.

The result of IDEO's expertise proved a success. "Out of this," Brown says, "HBO did some early deals with mobile phone companies which they might not have done if they had not taken the approach."

So how does it all work? Brown gives the processes scientists use as an example of how design thinking flows. "Design and science have some very fundamental principles like experimentation, evolution and hypotheses," he explains. "I think the big difference is that designers tend to use people as a starting point rather than science or technologies."

And compared to the academic mode of critical thinking, designers can't be any more different. "If critical thinking is about pulling initial parts apart in order to understand it from every perspective, then the other thing we do as designers is put things together and understand what they might be like," he explains.

Beyond that, it's all in the fieldwork. Instead of surveying consumers, study them. Follow them as they enter the building, try to see what they see and what the stumbling blocks are. Human data is something IDEO believes in; and with the data, Brown says that rapid prototyping is what counts in dealing with problems.

![]()

Practice, then, is what design thinking encourages - and with that comes Brown's view that design thinking isn't as high-brow as it's made out to be. "It's an attitude more than anything else," he says. It's about that appetite for discovering new things and finding more imaginative ways to cure existing problems. This, Brown suggests, can apply to everything.

But if design thinking can apply to anything, does that mean the death of the designer? Perhaps what Brown and IDEO are getting at is that the designer, in going 'small', has already died. Design thinking didn't kill designers - it rebirths them.

This article was originally published on TAXI: The Global Creative Network and has been republished with permission.

Iliyas Ong writes and handles editorial assignments for DesignTAXI.

"The problem with design," declared IDEO president Tim Brown at a lecture in Singapore recently, "is that it got small." He is speaking about 'design thinking,' a philosophy that aspires to make design 'big' again. Before his talk, Iliyas Ong sat down with Brown to find out more about his beliefs as a designer and innovator.

The Palo Alto-based IDEO is one of the largest 'design consultancies' around, with offices in Chicago, London, Shanghai and other top cities. Among its leaders include David Kelley, Stanford professor who helms the d.school, and Bill Moggridge, inventor of the world's first laptop computer. Voted by Bloomberg BusinessWeek as one of the top 25 most innovative companies in 2006, the firm, amazingly, does consulting work for the other 24.

IDEO isn't your normal design studio. There are no typography-obsessed graphic designers fretting over kerning, no web geeks arguing about Flash and HTML5. Instead, IDEO goes back to the earliest tenet of design: solving problems. It helps companies find innovative ways to develop and grow, be it by reshuffling its corporate infrastructure or oiling up service practices. And it uses 'design thinking' to do so.

"At its simplest level," Brown explains, his tone sprightly despite the jet lag from an eight-hour flight, "it's about using the processes that designers have used for many years but applying them to a broader set of challenges both in business and society."

If it sounds vague, it probably is. Brown confesses to have not "ended with any definition" to design thinking, even after publishing his acclaimed book, Change By Design, on the topic.

One thing's for sure, though: Brown knows exactly what went wrong in the design world. "Design used to be big. But then designers got preoccupied with creating small, nifty objects," he says. When Brown talks about 'big', he isn't talking about size, or scale, or depth. It's the totality of experiences that he - and 'design thinking' - refers to.

That cup you're holding, the MacBook humming on the table in front of you... these objects are works of design, but that's that. Design isn't about a fancy new computer or any 'revolutionary,' 'magical,' or 'cool' product.

Design is a "much more complex thing than any single object", Brown insists. It's about solving the problem of distributing clean water in poor countries, coming up with more efficient ways to direct human traffic in buildings, realising untapped channels of communication in trade. Design is huge.

"Designers have known this for quite a long time," Brown said. "But the business world and the world in general is just starting to understand that. Businesses especially started to realise that it wasn't good enough just to design a good product. If the service around the product was no good, or if the brand or communications were no good, you have to start thinking of them all together as an experience."

And that's where design thinking comes into play. It helps people and brands map out and focus their energies into innovation, a practice much-needed today. "As the markets opened up and technology sped up, companies get disrupted fast," Brown argues. "So whereas businesses 50 years ago could be somewhat complacent, no company could do that today."

Design thinking, then, isn't a panacea to business woes - innovation is. "It's an essential nature of all organisations if they want to be healthy and successful, that if they don't grow and change and innovate, they'll be commoditised," Brown states confidently. "There are only two potential futures for any organisation: either you innovate and grow, or you get commoditised and ultimately die."

A trip through IDEO's client list reveals a longstanding tradition of providing innovation to companies that need it most. The consultancy worked with HBO a few years ago, a time when the YouTubes and Hulus of the online world made HBO seem old and even worse, obsolete.

"HBO was very interested in looking at a design-based approach to understand how they could show up on new networks instead of being just a cable network," explains Brown on the spark HBO needed to stay on top of the media game. As a result, IDEO strategised new services and experiences the cable company could give its customers - how they could show on mobile phones and on computers, for instance.

The result of IDEO's expertise proved a success. "Out of this," Brown says, "HBO did some early deals with mobile phone companies which they might not have done if they had not taken the approach."

So how does it all work? Brown gives the processes scientists use as an example of how design thinking flows. "Design and science have some very fundamental principles like experimentation, evolution and hypotheses," he explains. "I think the big difference is that designers tend to use people as a starting point rather than science or technologies."

And compared to the academic mode of critical thinking, designers can't be any more different. "If critical thinking is about pulling initial parts apart in order to understand it from every perspective, then the other thing we do as designers is put things together and understand what they might be like," he explains.

Beyond that, it's all in the fieldwork. Instead of surveying consumers, study them. Follow them as they enter the building, try to see what they see and what the stumbling blocks are. Human data is something IDEO believes in; and with the data, Brown says that rapid prototyping is what counts in dealing with problems.

Practice, then, is what design thinking encourages - and with that comes Brown's view that design thinking isn't as high-brow as it's made out to be. "It's an attitude more than anything else," he says. It's about that appetite for discovering new things and finding more imaginative ways to cure existing problems. This, Brown suggests, can apply to everything.

But if design thinking can apply to anything, does that mean the death of the designer? Perhaps what Brown and IDEO are getting at is that the designer, in going 'small', has already died. Design thinking didn't kill designers - it rebirths them.

This article was originally published on TAXI: The Global Creative Network and has been republished with permission.

![]()

About the Author

Iliyas Ong writes and handles editorial assignments for DesignTAXI.About TAXI

TAXI, a participant in the , is the global creative network of today, a meeting place for creative professionals around the world to connect with each other, stay current with industry movements, and showcase their works towards prospects and opportunities.

related

articles

03.14.2022 Features

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

05.27.2020 Features

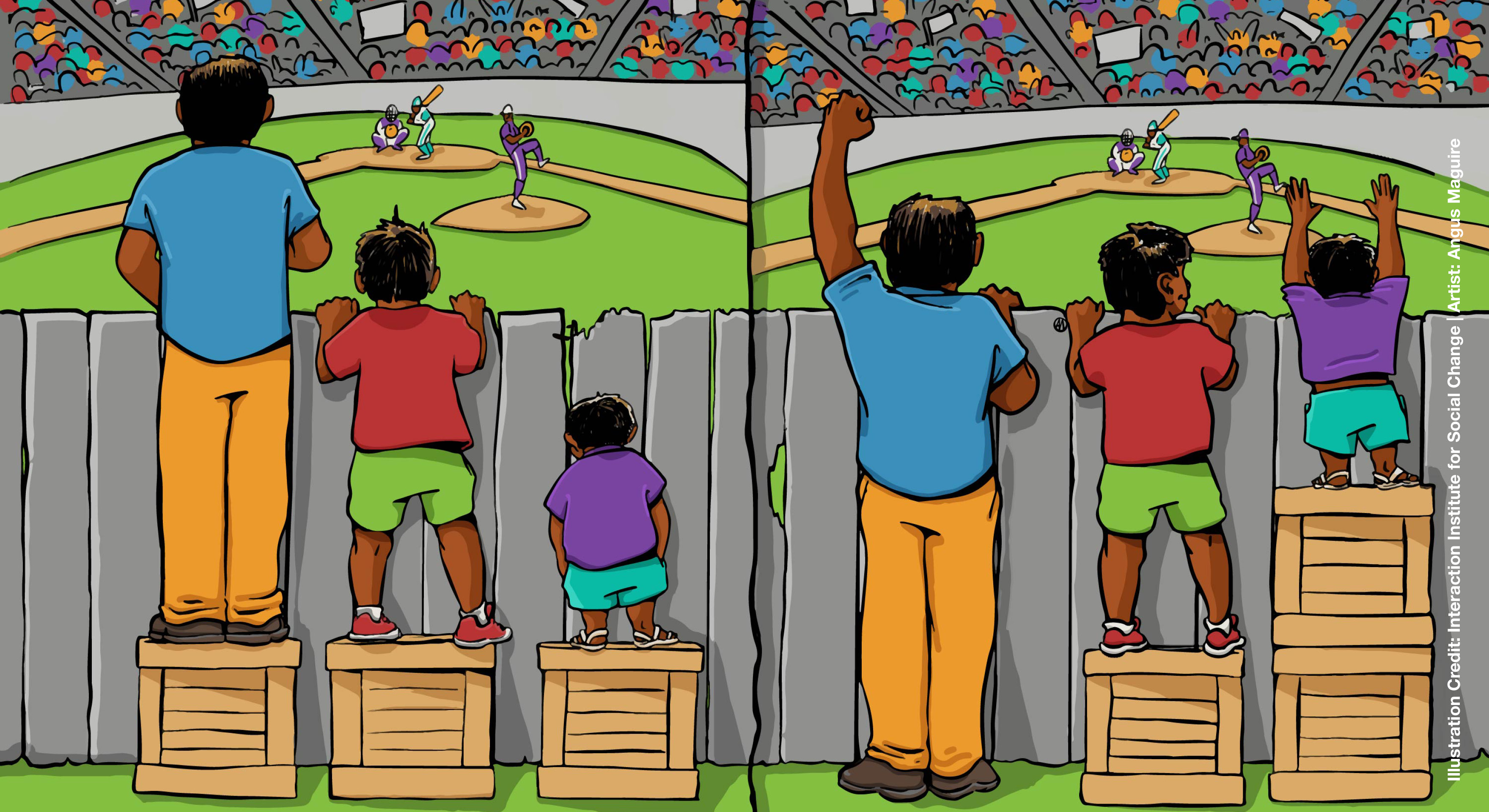

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

05.16.2017 Features

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

12.14.2016 Features

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)

05.11.2016 Features