feature | mandela poster project (part 2)

14.07.2015 Features

Photo credit: Basil Brady

In further celebration of Nelson Mandela International Day, 18 July, ico-D is releasing a second article about the Mandela Poster Project.

In Part 2, we understand how the MPP formed viable partnerships between the Nelson Mandela Children’s Hospital Trust and ico-D. This was part of a process aimed at evaluating the "right criteria" for achieving a project that was both design-focused and socially entrepreneurial.

Read the second feature here:

Mandela Poster Project (Part 2)

The social impact of the Mandela Poster Project is innovative and far-reaching. The project team was brave enough to embrace a simple question: “What can happen if…” as a mantra to innovate, challenge and explore endless possibilities for the project to thrive and benefit communities.

by Madi Hanekom

originally published in Contributoria July 2015

This is the second in a series of three articles about key aspects of the inspired initiative, the Mandela Poster Project (MPP).

The first article, told the story of the birth of the project and its planning and implementation to honour the man fondly known the world over as Madiba. The second article focuses on the various aspects which made the MPP a noteworthy example of a successful social entrepreneurship undertaking by the manner in which it challenged conventional parameters of business management practices and the ways in which it addressed limitations by implementing creative ‘designerly’ thinking principles.

The concept of social entrepreneurship / social enterprise

To situate the MPP within the framework of a social entrepreneurship / social enterprise project, understanding the parameters of what constitutes such type of project is important.

But what is the meaning of the concepts social entrepreneurship and social enterprise? From the literature it becomes clear that there is no consensus regarding a universal definition. What is clear though is that it is accepted that, where conventional entrepreneurs establish business ventures in the hopes of making a financial profit, social entrepreneurs are concerned with the social impact of their projects (therefore not profit driven). This kind of project is also characterised by a strong component of independence, democracy, participatory governance, and acting in general public interest. And more importantly, implementing alternative approaches to challenge stale management constructs by embracing unconventional project management tactics and philosophies by simply asking: ‘What can happen if…’ which inherently solicits a plethora of desired outcomes – be they achievable or not.

Social impact can be described as the extent to which an organisation or project’s activities positively affect the target group/community through an improvement in their quality of life. This improvement and change can be in various areas, for example, civil rights, food security, housing security and artistic and cultural expression.

In some discussion fora (like the European Council of Associations of General Interest) the opinion is held that the preferred term to be used is social enterprise, not social entrepreneurship. The thinking behind this includes the required focus on the social impact of a project as well as the desire to support all sections of the lifecycle of a project – not just the stage of entrepreneurship.

In the world of design thinking specifically, which is the ambit of the MPP, the social enterprise terminology (rather than social entrepreneurship) is commonly preferred when writing and talking about improving lives by designing for social impact and also through incubating start-up projects. As Hunter (2013) says, “Design, through nicking many of the best bits of ethnographic practice, helps us to understand and deliver what people need and want, its creativity imagining new possibilities. Design, therefore, has much to bring the world of social enterprise. What social enterprise gives back in return is the concept of impact – not letting designers get away with defining success as ‘shipping a lot of units’ but truly trying to understand if they have improved life, made no impact, or made it worse.”

For purposes of this article however the term of social entrepreneurship will be used in its broadest interpretation to address social impact and to include all phases of the lifecycle of the MPP and its application of the “What can happen if…” question/aspiration.

Due to its perceived and achieved benefits, the activities generated through social entrepreneurship is currently receiving focused attention worldwide in respect of targeted projects, case studies on the planning and implantation of these projects, academic research, and learning programmes at NGO/NPOs and universities.

And these types of projects are also increasingly being subjected to some form of evaluation to assess their success in terms of a number of criteria.

Criteria for assessing a social entrepreneurship project

As there is no universally accepted definition of social entrepreneurship there are also not generally accepted criteria to measure the success of such projects and therefore no international benchmarking and best practice.

The fact that there is no ultimate definition and criteria allows for a degree of flexibility in interpretation when dealing with social entrepreneurship projects. In fact, investigating the MPP from a social entrepreneurship perspective asks for an understanding of it also specifically being a project anchored in design thinking, which asks for a creative approach. “Design thinking is a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success,” says Tim Brown, president and CEO of IDEO (one of the world’s leading design firms that takes a human-centered, design-based approach to helping organizations in the public and private sectors innovate and grow.) Ultimately, the designer’s core toolkit again boils down to its practitioners’ inherent ability to ask and respond to the “What can happen if…” challenge/aspiration.

But allowing for flexibility in terms of interpretation does not mean sacrificing meaningful and well-tested principles related to the thorough planning, implementation and monitoring of projects executed within the world of business. It does however mean that any discourse on assessing the success of a social entrepreneurship/social enterprise type project in the field of design (such as the MPP) should include thinking outside the business box (which tends to focus on a culture of process efficiency) and take on board a process that promises to deliver on creativity (Nussbaum, B. 2011).

From the available literature, I have distilled seven generic criteria, phrased as questions, below against which I evaluate the MPP from the perspective of a social entrepreneurship project, with special emphasis on the project’s social impact. The point of departure for generating these criteria is rooted in sound business principles as well as principles applied in social entrepreneurship projects implemented in, for example, South Africa. But none of these projects were communication design projects like the MPP and due cognisance is therefore taken in this article of the natural way in which the designers and other team members approached conceptualising and implementing the MPP.

The Mandela Poster Project viewed as a social entrepreneurship project

MPP has a somewhat different narrative than most other social entrepreneurship projects described in the literature as it had a very specific vision and objectives requiring a specific tailor-made creative response within a short space of time while achieving a fitting social impact, and this comes through in its assessment against the stated questions.

What is the need for the project to exist and is its vision and objectives articulated clearly?

The MPP was born from a specific need identified by two South African designers, Mohammed Jogie and Jacques Lange on 10 May 2013. Their vision was to create an innovative communication design project which would stand in celebration of Nelson Mandela’s 95th birthday on 18 July 2013 and also serve as fundraiser towards fulfilling Mandela’s final legacy wish: the establishment of the Nelson Mandela Children’s Hospital in Johannesburg.

Through their creative drive a poster project was conceptualised with the main objectives of, firstly, sourcing 95 exceptional and originally designed posters from designers around the world depicting each contributor’s view of Mandela, his values and his extraordinary legacy and, secondly, to generate a specific amount of funds towards building the Hospital: mandelaposterproject.com.

The fact that a defined need, vision and objectives were formulated clearly for the MPP contributed hugely to its successful execution.

Is the project based on an innovative entrepreneurial idea that aims to have a positive and concrete social impact?

The MPP showed admirably what an innovative entrepreneurial idea can achieve if it is planned and implemented well by a dedicated team, even if put under exceptional time and other unforeseen challenges, as well as the extent of the positive social impact it can attain.

The innovativeness of the MPPs entrepreneurial idea stems from many factors. It includes the choice of posters as the medium for the project (the format lends itself to striking creativity on the part of the designers and extensive impact, catching a person’s attention in a short space of time and holding it for long after the viewing) and the way that social media was harnessed to optimally and immediately reach designers in just about every corner of the world. It also includes the speedy mobilisation of a team of highly skilled and motivated people to plan and implement the project within an extremely tight timeframe, the linking up with key stakeholders such as the Nelson Mandela Children’s Hospital Trust (NMCHT), partnering with businesses such as Hewlett-Packard who sponsored the production of the posters, and the utilisation of global networks of designers who gave their unqualified support to the project and spread the word about it to ensure the MPPs widest possible showcasing internationally.

The social impact of the MPP has proven to be far wider than what could initially been foreseen. The humble beginnings of this design-led idea was to celebrate the life of Madiba and his contribution to humanity by collecting 95 exceptional and originally designed posters from around the world honouring his lasting contribution to humanity and celebrating his 95th birthday. This however changed radically as the project unfolded. The idea was almost immediately also broadened to include a fundraising focus to support the establishment of the Hospital legacy project.

Soon after the MPPs launch the project went viral through personal networking and utilising social media platforms. The launch team was flooded by interest from international designers, international mainstream media, making it clear that the project was going to have a reach far wider than initially anticipated and providing a springboard to substantially increasing its anticipated social impact.

The impact on the international design community was also huge, providing designers with an opportunity to express their views about Madiba, to showcase their work internationally and to contribute to fund raising for the Hospital. Through an astonishing explosion of interest, more than 700 posters by designers from over 70 countries were submitted within the space of 60 days. Posters were received from all inhabited continents, constituting an impressive global response.

Strong interest was soon shown to showcase the posters and the 95 Collection would have either been physically exhibited or presented digitally at more than 35 venues and events in 12 countries by November 2015.

“Very seldom in South Africa’s – or even the world’s – history have we seen the power of design as it has been embodied through the Mandela Poster Project”, says Gavin Mageni, group manager of the South African Bureau of Standards’ Design Institute, which bought the master set of posters.

When the Hospital is completed in 2016, the ZAR 1 000 000.01 contribution that the project made towards the funds required to establish the project, will furthermore resonate in the children who are treated at this first class health facility, one of only five dedicated paeadiatric hospitals on the African content.

A further incalculable social impact lies in the source of delight that the project was for all who worked on it: the team, the many designers who participated as well as the thousands of people who viewed (and are still viewing) the posters and people who also use this project as an opportunity to talk about the life of Madiba, his legacy to the world, his ability to forgive, his deep sense of selflessness and altruism and a deeper understanding of what constitute freedom, reconciliation, appreciation of cultural diversity, justice and equality.

The MPP also succeeded in raising awareness, not only of Mandela and what he stood for, but of South Africa in general and, specifically, the power of communication design.

What difference would a dedicated leadership team, with clearly defined roles and responsibilities, make to the successful execution of the project?

It takes very special and dedicated people to conceive and successfully implement a social entrepreneurship project. Gregory Dees and Mariam and Peter Haas (1998), developed the following definition regarding social entrepreneurs which captures the essence of such change-makers:

“Social entrepreneurs play the role of change agents in the social sector, by:

· Adopting a mission to create and sustain social value (not just private value),

· Recognizing and relentlessly pursuing new opportunities to serve that mission,

· Engaging in a process of continuous innovation, adaptation, and learning,

· Acting boldly without being limited by resources currently in hand, and

· Exhibiting a heightened sense of accountability to the constituencies served and for the outcomes created.”

The initial partnership of two individuals, who conceived the MPP, rapidly grew to include a team of 15 volunteers, now known as the Mandela Poster Project Collective (MPPC). These team members were sourced from diverse cultural and professional backgrounds to ensure that all areas of expertise required on a project of this nature and who gave freely of their time and know-how over the last two years.

The organisation of the team was highly democratic and there was no team leader. But everybody on the team knew exactly what was required of them in terms of scope of work and knew when to collaborate with other team members and when to forge ahead with their own areas of responsibility. Instinctive dovetailing was a critical success factor and there was also agreement to trust each other’s abilities and judgements unconditionally – sometimes regarded as a risky management practice, but that is what design-thinking methodology allows teams to do.

The team consistently demonstrated a strong component of independence, democracy, participatory governance, and acting in general public interest while remaining focus on the desired outcomes of the MPP. It is clear that this dedicated team was crucial to the success of the project and that each individual had an excellent understanding of his/her role and responsibility.

Is an upfront agreed formal structuring of the project processes necessary and should all resources be in place before the launch of the project?

The team found itself having to deal with a so-called wicked problem (a complex problem for which there is no simple method of solution) in the sense that it had no organisational infrastructure or financial resources (in fact, no budget whatsoever). Nevertheless, the MPPC acted boldly to overcome the shortage of resources and found ways and means to plan and implement the project from a lean platform of available resources and within the time frame required.

The project, of necessity, needed to be planned and implemented on a fast-track basis due to the severe time constraints (the team had only 60 days – May to July 2013) to give effect to the detail planning and implementation of the project, and deal with the massive interest the project generated globally almost from day one. The team found creative ideas in a very short space of time to ideate solutions for the project (literally in the first two weeks of the project start-up). Says Lange: “We learnt and adjusted plans throughout the process.”

Although there was no formal upfront agreed written business plan, the team members' extensive expertise at senior level within their chosen fields and their extra-ordinary high level of commitment, meant that this was not a stumbling block. As creatives they also relished working in an environment where everything was not done according to a predetermined plan. It allowed for creative ideas and solutions to flow unhindered but with appropriate checks and balances put in place to ensure that the project did not go off the rails. For instance, a well-thought through structured three-phase curatorial process was followed to narrow down the 700 posters received to the final 95 which was included in the collection. “One of the other strengths was that we had our ducks in a row regarding legal matters right from the outset because we knew that copyright was one of the most critical assets that we were dealing with and the project and team’s credibility hinged on this in totality,” says Lange.

The project made optimal use of technology and successfully tested the viability of building a large, special interest virtual community in a limited time frame. The team chose their solutions based on practical considerations but also based on powerful ideas.

The MPPC early on in the project cycle identified the key stakeholders in the project and opened up effective lines of communication. The MPPC also kept up extensive and regular contact amongst the team members to discuss matters and to ensure that the implementation could go ahead in a meaningful way. The team relied heavely on communication technology such as email, social media, Skype and the Basecamp project management app, since the members were based in different cities and continents which meant that physical meetings were not possible.

How important is the identification and involvement of the key stakeholders to the success of the project, including the duration of their involvement?

The project team early on formed strategic partnerships with the Nelson Mandela Children’s Hospital Trust as official project beneficiary and ico-D (International Council of Design) as official promotional partner.

Other interested and affected parties in respect of the MPP was predominantly the international design community, strategic business sponsors such as Hewlett-Packard (production), Madlela Gwebu Mashamba Incorporated (legal services), Society of Graphic Designers of Canada (sponsor of the Basecamp communication and project management app), University of Pretoria (exhibition partner), SABS Design Institute (exhibition and promotional partner and eventual purchaser of the master set of posters) and various other exhibition partners and sponsors. The local and international media also actively supported the project and as such can be viewed as having played a specific role in the project as a stakeholder.

Participation in the MPP was open to all designers and contributors agreed to donate their poster designs to the Trust. Participants also agreed to allow the MPP to exhibit and reproduce limited copies as part of its fundraising efforts on behalf of the Trust.

In general there was a strong and sustained emphasis on inclusiveness of key project stakeholders. Long term involvement with stakeholders was not a requirement for the distinct phase of the project as each had a clear start and end date which automatically determined the timing and duration of involvement with specific stakeholders.

The MPP is an excellent example of a multi-stakeholder, cross-sector partnership project.

How is the sustainability of the project defined and implemented?

Sustainability is often defined in business environments in terms of the financial and operational sustainability of a project. But under certain circumstances there are other types of sustainability that are crucial, which is especially true in the case of the MPP.

The nature of the project asked for a different approach which did not require long term sustainability. As Jogie explains: “The MPP is a design-led initiative, it has a very specific format and brief, and it has a very specific desired outcome.” Once this outcome (celebration of Nelson Mandela’s 95th birthday and his life through a poster project, and having served as fundraiser for the Hospital) had been achieved, there was no real need to further keep the project alive in its original format. The team’s structure and focus has now shifted to other dimensions which include managing an international travelling exhibition schedule; case study presentations; the design of a font based on Madiba’s handwriting; the development of a book; and the detailed archiving of the project. Specific members of the team remain in place to manage this second phase of the project.

But the MPP subsequently seems to have taken on a life of its own and resonates far wider than just the design community. It would therefore not be surprising to in future hear of further innovative ways in which the MPP and its creative processes will be applied for learning purposes, thereby extending the intended lifecycle of the project.

However, a key sustainability measure for the MPP is its long term contribution towards cultural heritage, inter alias through the posters which will be made accessible to the public at the SABS and at the Hospital, once built. The cultural impact will furthermore also reach far wider as the project’s enthusiastic uptake by designers from different cultures worldwide, and the resultant varied images they portrayed through their posters strengthens our grasp of the culturally diverse ethnosphere (defined by anthropologist Wade Davis as “the sum total of all thoughts and intuitions, myths and beliefs, ideas and inspirations brought into being by the human imagination since the dawn of consciousness”) and that it is of equal importance as that of the diversity of the natural biosphere. The concept of the ethnosphere provides a “framework for considering the world’s cultures that emphasizes their significance, diversity, complexity, and interrelatedness – as well as their vulnerability”. The vast and diverse body of work that the MPP generated assists in defining Madiba’s legacy also in terms of a diverse spiritual web of life which is critically dependent on a multiplicity of voices.

Future replication and scalability of the project is desirable.

The MPP was not designed with replication and/or up-scaling in mind. But it would be interesting to see the extent to which future initiatives with characteristics similar, or somewhat similar, to the MPP, would make use of the approach followed by the MPP. The MPP has subsequently been included as a case study on social entrepreneurship and design citizenship in books, magazine articles and conference presentations.

Conclusion

The MPP should be viewed as a prototype project, especially in the field of design, where a creative idea is generated, needing to be made a reality in a short space of time, and dealing with unexpected challenges and opportunities on an almost daily basis. This prototype is an interesting example of a successful social entrepreneurship project executed on a fast-track basis and effectively and efficiently accessing crowd-sourcing by means of social media.

It is also notable that the team implemented task plans and resource determination very fast and executed and delivered within two and a half months on the first promise (the 95 Collection) and on the second objective eight months later (securing the fundraising).

Although the evaluation of the MPP might give the impression that the project was executed flawlessly and that everything proceeded without a hitch, the team was acutely aware of some gaps and weaknesses in the planning and implementation of the MPP. Some of these shortcomings were: insufficient marketing undertaken in the initial phase of project; not anticipating from the outset that the project would grow so quickly and fully preparing for such eventuality; allocation of an extremely large work load to team members which led to them being under constant intense pressure while also having to cope with managing their own careers; the team could have benefitted from sourcing more members to assist with executing the scope of work; and the preparation of a written up business plan at the launch of the project would have assisted to guide the activities. It is also recognised that there was an opportunity lost to raise further funding for the Hospital through, for example, selling individual posters to people (many who asked for this), printing T-Shirts, etc but the upfront agreement was that the focus of the project would not be a commercial one and the team went all out to fiercely protect the integrity of the project in this respect.

In general, project teams could potentially add great benefit to their projects by allowing themselves to think outside the box filled to the brim by standard business approaches applied in the planning and implementation of projects and asking a simple question, without limitations or expectations: “What if we follow a different approach?” The answer might pleasantly surprise them, just as it did the team responsible for the MPP.

Read the original article here.

Read part 1 | Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela – honouring an icon through an innovative poster project .

Visit the official MPP website at mandelaposterproject.com

About the writer

Madi Hanekom is a freelance writer as well as executive and leadership development coach and mentor. Madi writes about business related matters, lifestyle, gender, coaching and mentoring, travel and restaurant reviews and her articles have been published in numerous newspapers and magazines. As coach she has a wide client range which includes senior managers in the government, private and non-government sectors. Madi is a full member of the Southern African Freelancers’ Association (Safrea), Coaches and Mentors South Africa (Comensa), International Coaching Federation (ICF) and Project Management South Africa (PMSA). She has over 30 years experience in the corporate, private and non-government sectors and her qualifications include Masters in Business Administration, B.Comm Hons (Economics), Post-graduate certificate in coaching psychology and Certificate in magazine journalism.

relatedarticles

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

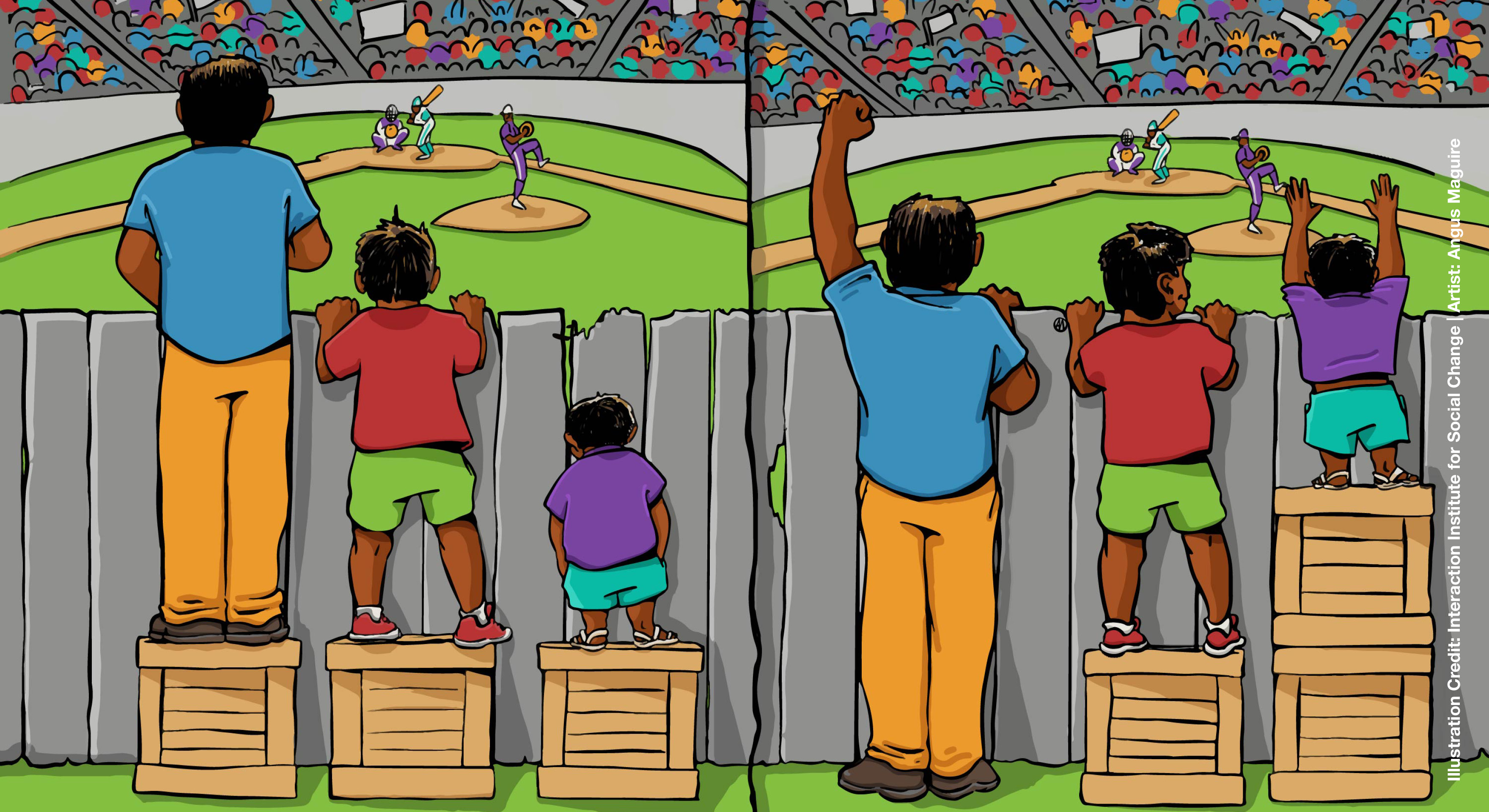

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)