designing towards ancestors: a no-brand future

12.08.2015 Features

Frida Larios, Author and Founder of New Maya Language and the project YourInteriorAnimal.

In addition to featuring the 2015 IDC interview between Don Ryn Chang and Frida Larios, ico-D has asked Frida Larios to be the first guest curator for our series of ico-D instagram takeover. Follow Larios' Insta-story beginning the week of 17 August 2015 at Instagram account: @theicod.

//During the same week, Larios' work will appear in her solo exhibition Animales Interiores at the Museo de Arte de El Salvador. See YourInteriorAnimal.

The fourth special guest for the 2015 International Design Congress Interview Series conducted by Don Ryn Chang is Frida Larios. The interview contains discusses her design philosophy and projects, which includes an innovative approach in communication design to reinterpret the ancient hieroglyphics of the Maya.

Don: Frida, I was reading some of the interviews you did in the past and was impressed because a common word that comes up is that you are a multi-tasker; you are an athlete, a researcher and you lived a very diverse life. So my first question to you is, can you briefly introduce your diverse, dynamic, multi-activity, multi-cultural journey to becoming an indigenous communication designer? I don’t know if that’s the right term but maybe you could also refine that as well…

Frida: That’s a nice term. You know I started sports in a German school in El Salvador only because it was my neighbourhood school and they had a good quality of academia and my parents thought that learning two other languages apart from my native Spanish would be enriching. It was there that I I was introduced to volleyball. But before that I was a gymnast as well.

Don: Right, I read that too. You were part of the national team as well.

Frida: I’ve practiced gymnastics since I was five. And I also competed internationally. As a volleyballer I was on the school team and was called to the under-18 national team. That experience introduced me to my first encounters with other countries as a 16 and 17 year old. We traveled to neighbouring countries, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, México, but in a very poor situation because it’s hard to fly teams of 12 people, plus coaches. And then beach volleyball became an Olympic sport. El Salvador decided to promote it and invest in it. That’s when I changed from indoor to beach. I loved the sand and the natural outdoors, and the fact that it only took two players, which made it more sustainable.

In the meantime, I was studying graphic design in the local Universidad Dr. José Matías Delgado applied arts school. A big change and opportunity came when I left my home country and went to England, to finish the BA in Cornwall, at Falmouth College of Arts, now University College Falmouth, in the southwest tip, where Barbara Hepworth, the famous English sculptor, lived and practiced. There was an embedded art tradition there, influenced by the distinct endless seaside landscape. I really thought I would be able to play beach volleyball there, and that’s why I picked Falmouth, very naively! It was absolutely cold, but we still tried to do play a little in the handful of summer days.

"I became enamoured with the English preciseness, and the English process of design: where it takes one or two years to develop a single project. It’s a different approach because it’s about the organic research process, not the final outcome, as opposed to how it was in the US. I liked that freedom and sense of exploration."

Then I came back to El Salvador. I went on to work at a small design studio with my sister called Ideas Frescas (Fresh Ideas). It had a little juicy watermelon as a logo. Having my own office allowed me to design my own time, and so I practiced beach volleyball, trying to do both: part-time. When you say multi-tasking, it might be apt!

I was traveling to London to do some design studio practices there and then I got a Fulbright scholarship from FANTEL - Harvard LASPAU granted by my home country’s government. I applied to do a Masters degree with a vernacular, graphic language project in mind. It’s not the project that came to be in the end, but the outcome was a similar proposal. With the awarded funds, I went back to England, but this time to London. I studied for the Master’s degree and went on to teach as an Associate Lecturer for Camberwell College of Arts and the London College of Fashion, both a part of the University of the Arts London.

Central Saint Martins - where I realised the MA in Communication Design, Type and Language pathway, was directed by Andrew Haslam, who co-wrote Type and Typography with Phil Baines, who I notice is an Open and Create Communication session speaker alongside Saki Mafundikwa and yours truly, during 2015 IDC - was very close to the British Museum. In the Meso America wing, I was to find the most intricate carved lintels: human size stone sculptures, book-like, right there in the middle of London, and faraway from my Central American home.

In that context, I discovered the central point of my project: that Meso America – ancestral Central America – was united by the Maya script, and that every city-state had the knowledge (through the scribes/the artists) of the hieroglyphs. This written language is not in use nowadays because the Spanish burnt all the books, it is technically dead, even though Maya peoples are living communities. The Spanish colonial takeover was very rough – a cultural assassination, basically.

"Apart from celebrating and preserving an ancestral visual language, I thought it would be very interesting to look at it from a communication design perspective, to redesign the logos-glyphs, and it seems that no one had done it before."

Don: You made a very pertinent statement that Maya were the original graphic designers. So can you elaborate on that statement?

Frida: In my view, graphic designers are interpreters of information. They have to arrange the content in terms of typography, medium, and in terms of the subject matter. All these components are brought into a visual life in which everyone, or almost everyone, can understand a similar message.

In the same way, the Maya, within their own context, became a civilization in which the royalty or the elite needed to transmit messages and were also pursuing, in the same ways as the Romans, to establish an empire. So communication became key to achieving that political agenda. The government had what we know today as graphic designers - people who had to know what they wrote were writing about: history, mathematics, astronomy, book-keeping, etc., as well as the alphabet – the script, then also design the information: type-set and illuminate it, and, on top of that: produce the design in the most varied mediums, like – stone, ceramic, textile and paper.

It was challenging because this took place in a non-digital era. There had to be transmission of the script’s standardized code throughout the city-states, and dispersed kilometers apart between geographical settings as it was in other parallel civilizations - like in Korea. Of all these artistic records, there are only four scrolls (books) left in the modern world. Again, it is because of the crude Spanish colonisation and Christianisation. These remaining books were executed calligraphically. This is where the concept of my project came from, but it took me 10 years to find out that the outcome was in the process!

Don: This story has many similarities with how the Korean alphabet came into existence - when, almost 700 years ago, our King Sejong commissioned all the scholars to create a new written language which would be universal for the common man. I think it was a way to expand knowledge but also to communicate in a sustainable way, a similar type of communication design.

Frida: And that’s also very particular, that King Sejong The Great, 700 years ago, had such vision and determination to use communication design – typo-graphy, even – as a means of interpreting a spoken language, and, at the same time, to deliver cultural messages. An apt parallel to the Maya script, which was mostly syllabo-graphic, and to the New Maya Language project proposal - a designed system applied to meet contemporary needs. The major difference with the unique Hangul script is that the New Maya Language is logo-graphic and represents a very tiny proportion of the entire vocabulary as it once existed.

Don: To refresh my memory, the Maya culture existed several thousand years ago?

Frida: Yes, the Maya civilisation came to be around 500 BC. The script started its development around 200 BC, and by approximately 800 AD, the Maya city-states system became unsustainable for different reasons: environmental (due to resources exploitation), deforestation, mining, etc. This caused the citizens of these major cities to disperse to smaller communities. When the Spanish discovered this, and tried to kill the Maya cultural symbols, that it was kind of like the last drop of the glass being poured out. Even though the Maya culture, and the derived spoken languages, are preserved through living Maya peoples throughout the region, the script came to an end.

Don: That’s unfortunate. How does your project to promote the reintroduction of the Maya written language and its use in a modern context?

Frida: That is one of the project’s missions, even though there are a few local purists/anthropologists who oppose a re-design as they see it, as touching upon sacred science. But the majority, including living Indigenous communities that have been in touch with the project’s art, signage, book or children’s book in Honduras, El Salvador or Guatemala, as well as archaeologists and anthropologists, and especially, the communication design community through organisations like INDIGO, the Latin Design Ambassadors Council, and the 2015 International Design Congress, for which I serve as an Ambassador, have been extremely supportive. One of the next mid-term projects is to create a story-telling application for children.

Don: Will this app become available to everyone in the world?

Frida:

"Open knowledge is now available to the world through your personal mobile phone - if you are privileged enough to have a smartphone, that is. It would be downloadable on the internet, in keeping with the democratic values of the New Maya Language project. Accessibility and audience would depend on the partnerships developed to do this."

Don: That would be amazing.

Frida: Yes, it would be amazing! Of course, you need the right partnerships and funding. So that’s a challenge.

Don: This would be a great vehicle to promote indigenous culture like the Maya culture. The sort of sensibilities but also, the way they are communicated. And in a modern context also, because a lot of people have this misconception that indigenous culture is kind of more non-contemporary. So to show that in a contemporary context is important to also instil pride in an inherited culture for young people.

Frida:

"More and more we are losing ancestral messages. That’s part of what I want to discuss in June at the 2015 IDC Congress, is how mythology can effect and affect designers today and how that can be preserved."

And as you said: in a fun, creative, innovative way. Not merely reproducing, but re-creating ancestral knowledge that has application in the present. Children and youth only learn and absorb when they have a need to practice and use. For example they use language, numbers, science, cultural symbols, mostly through play, and this is when the young human brain gives birth to neurons and this is when the process of ancestral appreciation starts.

Don: I know you do a lot of lectures, but you also teach. For young designers living in North America or Central America, how would you convey to them the importance of indigenous, cultural identity in a world where we are being inundated media that tends to be more generic rather than inherently culturally- inclined?

Frida: This poses a challenge, but the media also has brought global messages, the standardization of visual codes, and it’s also brought a new imaginary and visual representations from different countries. Before, these codes didn’t have a voice. Now, they have an outlet and other people can find out about them.

In terms of how do you speak to youth about this…well, after 10 years of developing it, my final vision was to be able to communicate this to children. And, somehow, I have planted a little seed in the earth, which fulfills that objective of introducing the unique pebble-shaped forms, not only, of course, the content but lines and the myths of these people to the young audience of ages 4, 5, and 6. This is the exact age when the crop starts growing. They are fascinated because they are now in touch with these new shapes and ideas in everyday life, through a little book, puzzle and mythological narrative workshop. We, as Latin Americans, have been using the "foreign" Roman alphabet, which is not culturally relevant, it was totally imposed in the name of Christianity - in a way that may be similar to how the Chinese were being used in Korea before Hangul. Yes, that can be seen as a purist approach, but if the young were taught through their own roots, there would be more empathy and more inclination to use something to which they are organically connected.

Not much time has gone by. 2500 years is not too much time compared to 523 years since the Spanish colonisation.

"The process of recognising Indigenous pre-Columbian symbology is deeply embedded in the collective consciousness of children and youth. They want it and like it; they understand clearly that it’s theirs."

Don: You said “empathy,” which is a word I always try to emphasize. Having lived in not only Central America, but Europe, and also now living in the United States, as well as having lived as the son of a diplomat in many different countries, I think that it is very difficult to have empathy for other cultures or other languages. How do you see your role as an international designer? How can we increase different levels of empathy using the medium of communication design?

Frida: For one, it is important where Grass roots creation designs will be applied, and that it be understood that the community owns and appropriates them. The messages, the stories, the wisdoms and that new things come from this "mutualness,” so the designer becomes, in a way, both a student, an educator and a hand holder who creates human relationships.

This is the experience we had when we were living in Honduras in the Maya archaeological area of Copán. Every day, we were in contact with our Maya peoples over there, and witnessed their day-to-day life - heir necessities and their struggles, like living in a dirt floor, sowing maize and beans to have as only nutritional source. Children having coffee for breakfast, before school. Because sometimes there is no money to buy anything else. That feels like empathy.

"How do you use design as a weaving thread, is the big question?"

Don: You talked about social issues just now. We are not living in a so-called equal world, which entails of course different perspectives. How can communication design enable realizations of pertinent issues and how can we share that the environment is a critical issue everywhere in the world. How do we create awareness of protecting the environment or issues of sustainability or sharing wealth? What would you say about this to youth and designers worldwide?

Frida: I think the message to youth should be design less.

"Is there a real need for this design piece? Is there a real need to do this, or to even develop this project? Is there a real need for advertising? The latter is one of my big question marks."

Because then we go back to the idea of creating within the grass roots. Can a small Indigenous village in Borneo, who produce woven bamboo crafts, afford advertising? Do they need to advertise? Probably not. Who needs to advertise? Large, wealthy corporations. Also, small ones, since large ones invest so much in them. And some are attaching themselves to underprivileged populations’ stories, just to project a certain “advertisable” image, not because a movement has been born from within. It becomes key to have real intentions that can be “read” by audiences. This is the success of crowdfunding, for example. Crowdfunding is the new "advertising." That a small group of women in Malaysia could now share their story via crowdfunding and recruit partners. Technology accessibility is another subject, though...

Don: That brings to us a subject I worked on quite a lot - branding. Branding is sometimes considered quite unethical. Sometimes challenging. How would you recommend a more ethical way of branding for different institutions?

Frida: I would argue that the future is to not brand. Because branding is something that encapsulates and pigeon holes, and creates a visual image that probably doesn’t represent everyone.. And I would hope advertising is dead soon. Because you are paying, brands are paying for a one-way message.

Looking back to look forward is definitely a necessity. For example, every founding world civilisation was deeply aware of their role in the environment and understood their role within the different elements of nature. In fact, their creations were sourced from the native world. Everything had a balance. A calendar was based on the rhythms of seasons and agriculture, a women’s cycle, birthing, and that’s where the graphics came from. That is something to think about.

Don: So they were all inspired by nature.

Frida: Human sharing was absolutely conscious. There was this sense of dependence and reverence. Not of power and dominance, like today, where we’ve lost that connection. Waking up with the natural light of the sun, going to bed with the sunset that would save a lot of energy. But of course, like I said, it’s just a dream of the past. The world has changed and we have changed. Actually, no, the world hasn’t changed, we, humans, have changed it, for the worst, as I see it.

Don: Well Frida, I think we covered a lot of issues. This would be perhaps my final question: how do you see yourself evolving as a designer, artist, and multi-tasker moving forward?

Frida: The way I see it, organisations like INDIGO for example, the International Indigenous Design Network, of which you are aware of, but maybe some people are not, and which by the way dormant at the moment, in search of new funding. INDIGO is needed because these are the type of bodies that will host ideas to bridge the ancestral with the present and the future. So that is something I consider important. Also, in terms of a collective that creates and unites minds from around different regions, like you have said, the same issues come to the table every time.

Then, on a personal level, I would like to continue immersing myself in the Indigenous expression and representation universe. I think there are endless resources of ancestral visual mythology, “mythography”, is how I call it. I lwould like to continue to do that, and to keep innovating based on this knowledge.

For example, I am currently working on the forthcoming project of designing the uniforms for the El Salvador, Panamerican and Olympic team, in collaboration with the El Salvador Olympic Committee and a young Salvadorean fashion designer. The project ‘becomes a good window for communicating and trying to illustrate what ancestral-to-contemporary graphics look and feel like when worn.”

The bearers, in this case, the athletes, become the carriers of symbolic messages and can tell the root story, like in the first times. The Olympians will be identifying with certain picto-graphs: a series of underworld world animals from Meso American Indigenous mythology. Each athlete has selected one animal and its special “magic” to wear to the Panamerican Games inauguration ceremony on July 10, in Toronto, Canada. The Fish, the Turkey, the Dog, were part of the creation line-up. A Panam Games classified athlete said: “I am in between the Fish and the Turkey. I like the Fish because in a game you have to keep switching strategies, and you have to do this with courage. The Turkey, because you don’t know how the opponent will play you, and there is always the surprise element during a match.” She said this because the Fish “mytho-graphy” represents Courage and Change, and the Turkey: Surprise and Fighting.

“The whole “pick-your-own uniform,” democratic process deceives the idea of the uniform in itself, and is a point of entry to interest young minds in their visual past.”

Don: Sounds very exciting. Good luck with your project. Thank you for contributing and we look forward to your solid participation in Gwangju in October.

For more more information and regular event updates:

Visit the and the Congress website: 2015idc.org

Visit Frida Larios' website here and her new project www.newmayaunderworld.com.

* The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of ico-D.

relatedarticles

goodbye! and next steps for colleague and friend alexey lazarev

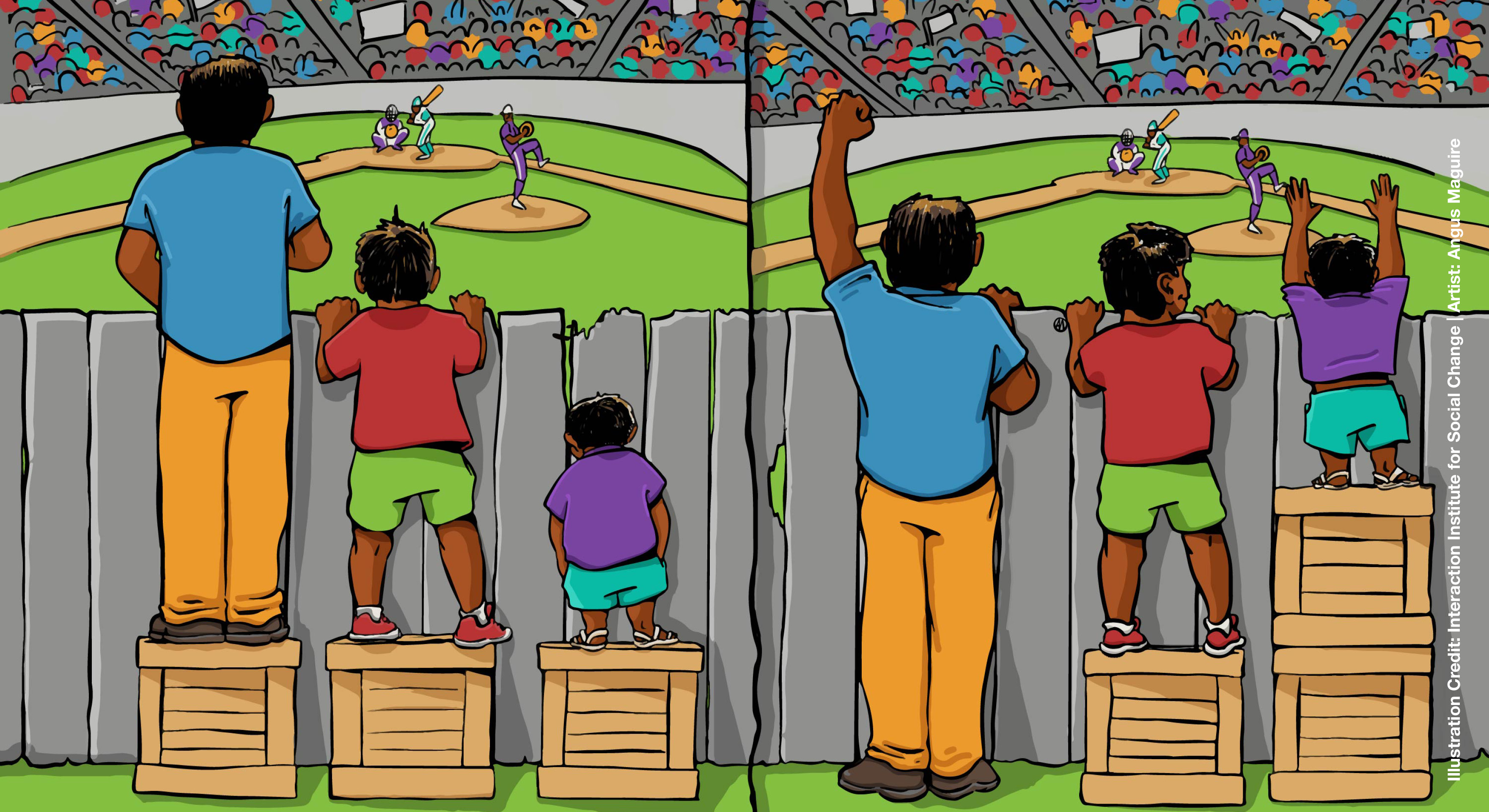

explorations in ethical design: meditations on equality

RCA launches new programme: MA Digital Direction

Interview | Ermolaev Bureau (Moscow)